Every year, at the end of spring, Paris welcomes the elite of world tennis. The screens are then covered with a crushed brick-colored background crossed by yellow balls. Between two matches, the cameras linger on the aisles of Roland Garros where a rather chic audience throngs. Amateur tennis player but professional economist, I went through them to discover the mysteries of international tennis competitions. Hasn't economic science promoted game theory and even developed a tournament theory? Are professional players sensitive to the lure of profit? Do they act as cold-blooded strategists and monsters?

The next winner of Roland Garros will pocket 2.4 million euros. Maybe it will be Rafael Nadal again, for the fifteenth time. Same amount for the one who wins the final. Polish Iga Swiatek for a third victory? Regardless, a little over 50 million euros will be distributed this year to players.

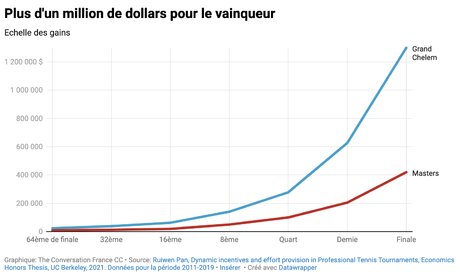

As with other professional sports, tennis does not only offer silver trophies to brandish in front of an exalted audience. Its particular character lies in the very large difference in financial prizes in the different rounds of the competition. The figure below provides an overview for the Masters tournaments as well as the Grand Slam tournaments (Roland Garros, US Open, Wimbledon and Australian Open).

.

.

Attract the biggest stars.

The prices serve a dual purpose. The first is obvious: attract players into the competition, especially the biggest stars. Obviously, in the eyes of the organizers of the four major tournaments, the prestige and international ranking points that they bring are not enough to ensure the presence of most of the top hundred players in the world. This particularly applies to the Australian Open due to its geographical distance. The second is perhaps less intuitive: getting players to give their best. Which implies that they make more effort in a match since victory brings them more money.

A small number of empirical studies have highlighted this sensitivity of professional players to winning. For example, it has been estimated that performance on the courts increases by around 1% when the differential doubles between the price awarded to the winner and that awarded to the loser. Or that the favorite of the match is 2.8% more likely to win when the differential increases by more than half compared to the average. Note that the proof is not straightforward. The players' effort cannot be observed as such. It is then assumed that the performance of the players or the level of play of the favorite reflects the efforts made, all things being equal.

From a theoretical point of view, this response of players to financial incentives is not surprising. Tennis competitions are organized as a series of successive matches eliminating the loser and allowing only the winner to continue towards a possible final victory. A tournament therefore, modeled precisely by the economic theory of the same name. It starts from the idea that an individual's performance depends on his talent and his efforts and that he adjusts these according to the expected gain (i.e. the amount of bonuses successively offered to the winners of the matches minus the cost of the 'effort). The competitor increases his probability of victory by exerting greater effort given the talent and effort of his opponent as well as his own talent.

Necessary inequality of the scale?

Tournament theory involves establishing a highly unequal prize scale. Let us reason absurdly by assuming that the price is the same for all duels. Individual effort would inevitably slacken from the first qualifiers until the final. Imagine for example that the prize for winning the quarters, semi-finals and final is 100,000 euros per match. A quarter-finalist can expect to take home 300,000 euros if they win all the events; but once he reaches the semi-final, he can only hope to win 200,000 and only even 100,000 if he reaches the final. The prospect of a decreasing expectation of winning would result in a decreasing effort as the tournament progresses.

To ensure constant effort from individuals from one round to the next, the price must increase from one round to the next. The theory of tournaments even suggests offering an incomparably higher prize for the winner of the final because once won, in the absence of a new duel before him, he no longer has any additional gain to hope for. The organizers of tennis competitions are undoubtedly not familiar with the economic theory of tournaments but in view of the figure presented above they unknowingly follow its precepts.

However, be careful not to be misunderstood. It is not a question of claiming that professional tennis players are Homo economicus. They certainly appear sensitive to the lure of gain, but it is obviously not their only motivation to exert effort to win their matches. The desire to win, the search for notoriety, the desire to mark one's era, or even simply the love of the game are also powerful incentives. No doubt even more than money, as the effects of only a few percent highlighted by the empirical studies cited above suggest.

Service strategists?

The serve is the only gesture perfectly within the player's hand. He is the master. It is up to him to act and not just react. It's up to him to decide where to place his ball in the opponent's field as well as the effect and speed he wants to give it, 257 km/being the official record to beat for men. Naturally, if the receiver knew this in advance, his return would be more effective. Hence the need to serve unpredictably on the opponent's backhand or forehand. And not to systematically serve on one of your flanks even if it is a little weaker.

Statistically, we observe that the probability of winning the point by serving to the right or to the left is almost identical. For example, out of ten matches during which former champions like Borg, McEnroe, Lendl or Sampras served 3,026 times, the server won on average 65 times out of 100 the point by serving on the right and 64 times on the left. This even though in these matches the servers served a little more on the right than on the left, a difference reflecting a more efficient service on average on this side.

Again, this is not a surprise to a theorist. An equality of probability is expected by game theory when, faced with uncertainty, decision-makers follow a strategy called “minimax regret”. The latter consists of minimizing the maximum number of regrets they may have when making their decision. In other words when the regret of not having chosen the best solution is minimal. The statistics just cited come from an article entitled “Minimax Play at Winbledon” published almost twenty years ago in the most prestigious academic journal in economics. Its authors model the theoretical game of the service point as a double choice: that of the server but also that of the receiver who prepares his forehand or backhand a little in advance, for example by positioning himself a little further to the right or to left on the baseline. The balance of this game is given by a precise proportion of right/left service: that for which neither the server nor the receiver has an interest in deviating because they would then lose more often.

The statistical equality of the probabilities of winning on the right and the left was recently confirmed over 3,000 matches and half a million service balls. It must be said that the 3,026 serves in the ten matches cited above had been laboriously collected by the researchers by watching them themselves. Since the introduction of Hawk-Eyethe electronic refereeing support system that reconstructs the trajectory of each ball and even allows viewers to see where it landed, a mass of data is now available.

Professional players, anxious like the others?

The perfect follow-up of a “minimax regret” strategy also assumes that the players arrive at the equilibrium proportion according to a random sequence. If this proportion is for example two thirds of services on the right and one third on the left, it is not a question of serving twice on the right then once on the left or vice versa and then repeating the operation. Professional tennis players do not conform to theory here. They tend to change sides too much compared to a machine that establishes purely random right/left sequences. They are not perfect robots.

An observation of humanity that is easily verified by everyone. Robots wouldn't grunt while hitting the ball like Monica Seles did in her time. Or would not follow, like Rafael Nadal, a long ritual full of tics before serving. More seriously, we observe in professional circuit matches that winning a point increases the probability of winning the next one. A feeling of reinforced confidence, no doubt. And conversely, losing the previous point increases the probability of losing the next one. A likely sign of growing anxiety.

Empirical work seems to show that it does not spare professionals. In a recent work published in Psychology of Sports and Exercisea trio of researchers looked at both points that follow an obvious error (such as a double fault on serve) and those that are crucial at a moment in the game (such as decisive game balls, set, and match), points for which the pressure on the player's shoulders is therefore the highest.

Half human, half robot.

The researchers then discovered that a crucial point following a missed ball was more likely to be missed than an ordinary point. And also that the winners of matches are no more immune to this reinforced effect of anxiety than those who lose them. If they win their match, it is not so much because of greater composure during crucial points but because they maintain a higher general level of play. A cognitive flaw which does not spare the commentators would make them systematically take the crucial successful balls as proof of composure.

There are, however, exceptions. In an essay on the typology of mentalities of tennis players based on data on nearly 1,000 players and three million points, an economist and a statistician showed that the great champions formed a category apart from their morale of steel. Among the men, there are a dozen players including Djokovic, Nadal and Federer who have won 56 Grand Slam singles finals between them. They serve decisive game points better and not less well, are less affected than the others when the previous point has been lost, and raise their level of play on the points allowing them to take the service from their opponent.

This last characteristic is also shared by Jo Wilfried Tsonga and Gaël Monfils, two players dear to the French public. Raising your level of play when necessary is also of course a trait common to great champions like Serena Williams (23 Grand Slam singles victories). The great tennis players are human robots. They combine the composure of the former and the mental aptitude of men and women to surpass themselves, and also, like the others, not to be insensitive to money.

I wish you good tennis games to come as a player in your club and a spectator or television viewer of the Roland Garros matches.

By Professor of economics, Mines Paris – PSL

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings